Jo Mynard and Katherine Thornton, Kanda University of International Studies, Japan

Mynard, J., & Thornton, K. (2012). The degree of directiveness in written advising: A preliminary investigation. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 3(1), 41-58. https://doi.org/10.37237/030104

Download paginated PDF version

Abstract

In this paper, the researchers analyse written discursive devices that learning advisors (LAs) at their institution use in order to give input to learners on their self-directed work. The researchers analysed written advising approaches by seven LAs throughout an eight-week period and coded the discursive devices according to their degree of directiveness. The results of the research indicate that LAs draw on a range of discursive devices and use varying degrees of directiveness when addressing the needs and learning stage of the students. The results have implications for LA training at the authors’ institution.

Keywords: advising, self-directed learning, written feedback, discursive devices

The field of Advising in Language Learning (ALL) is a developing area of applied linguistics and is in the process of establishing its own discourses and practices (Carson & Mynard, forthcoming). This paper has two main aims; (1) to add to the body of knowledge of advising discourse and practice, and (2) to understand more about the nature of written advising practices. Learning advisors (LAs), particularly ones new to the field, often experience difficulties knowing the appropriate approach to take when advising learners and how directive a stance to take during the advising process. A directive stance is one where an advisor or counselor intervenes in an obtrusive way. More research is needed in this area and the present study attempts to understand current practices at the authors’ institution in relation to the degree of directiveness adopted by LAs during the written advising process. The findings will provide insights for new and ongoing LA training.

Literature Review

Counselling and advising in language learning

ALL draws on a variety of fields which inform research and practice. The two main areas of professional practice which learning advisors draw upon are language teaching and professional counselling. There are variations in theoretical underpinnings that guide approaches to counselling (Nelson, 2008) and the approach most drawn upon in ALL is person-centred counselling which was established by Carl Rogers. The three underlying goals of this kind of counselling are respect, empathy and genuineness (Egan, 1994; Mozzon-McPherson, forthcoming; Rogers, 1951). Person-centred counsellors aim to develop and maintain effective self-concept (Colledge, 2002), personal fulfilment and self-actualisation. Other schools of counselling are not often referred to in ALL, but there may be merit in drawing on other approaches to counselling, in addition to other kinds of professional advising and coaching (Carson & Mynard, forthcoming).

Degrees of directiveness

Person-centred counselling is generally non-directive and counsellors adopt an unobtrusive role. Other forms of counselling such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) may involve more obtrusive interventions or advice-giving. Although many mainstream schools of counselling are largely non-directive, tensions have existed in specialized counselling fields and an examination of the discourse reveals that counsellors do actually give advice – albeit in subtle ways. For example in the specialist field of HIV counselling, counsellors were found to combine non-directive counselling practices with advice giving (Silverman, 1997). Similarly, in family planning counselling, counsellors were found to be skilfully negotiating issues related to health and family planning with clients (Candlin & Lucas, 1986). The counsellors seemed to instinctively know at what point along a continuum of directiveness to pitch their advice. The practice of alluding to advice without explicitly offering it is another subtle intervention technique in general counselling (Maynard, 1991). Furthermore, Feltham (1995) notes that features such as persuading and influencing in a non-directive way can also be used in counselling sessions.

Aims of ALL

LAs are usually trained language teachers with experience and knowledge that could be of great benefit to learners who are beginning to plan their own self-directed learning. Whereas the overall aim of ALL is to promote language learner autonomy (Carson & Mynard, forthcoming), the LA has to negotiate the difficult task of deciding when to provide input and suggestions and when to wait for a learner to discover certain connections by themselves. Allowing the learner opportunities for experimentation and reflection may increase the likelihood of a learner assuming a greater degree of control of the learning process.

Supporting self-directed learning

The self-directed learning modules used at the researchers’ institution have been described in more detail elsewhere (Mynard, 2010; Noguchi & McCarthy, 2010; Yamaguchi et al, forthcoming) so will not be discussed at length in this paper. The modules are optional, self-directed courses of work offered at the self-access learning centre (for a description of the self-access centre, see Cooker, 2010). There are a variety of module types available to all students at the university, but the current research focuses on a module offered to freshman students in their second semester called “Learning how to Learn” or LHL. At the beginning of the module, learners are assigned an LA who helps them to set goals and to plan and implement an appropriate course of self-study. The modules are referred to as “module packs” and are physical folders containing a learning plan and blank pages for documentation and reflection. The learners may include examples of their work in these packs. Each week, learners undertake self-directed independent work and submit weekly summaries and reflections on their work to their assigned LAs. LAs comment on the students’ work and reflections each week during the eight week period and also meet the learners individually twice during that time.

Written advising

The aim of written advising is to promote deeper-level reflection on the language-learning process (Mynard, 2010) and to guide the learner towards following a more effective plan which ultimately results in linguistic gain (for a discussion of the benefits of written advising see Mynard and Navarro (2010) and Thornton & Mynard, (forthcoming)).

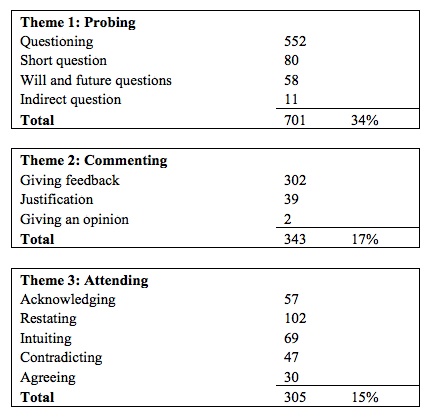

In a previous research study which analysed written advising contained in the LHL module packs of thirty learners at the same institution, the results (displayed in Table 1) showed that a range of discursive devices were used by LAs during the eight week period (Mynard, 2010, pp. 616-617). The second part of this study attempted to identify the written discursive devices that the learners felt most benefited their self-directed learning by asking learners to highlight the most beneficial written comments from their learning advisors after the module had finished. Analysis of the results indicated that a range of discursive devices were useful for their learning and no comment type was shown to be more beneficial than others. What appeared to be more important for the learners was that the LAs were targeting their written advising specifically to the learners’ needs and self-directed work (see Mynard, 2012 for details of the second part of the study).

Table 1. An analysis of written discursive devices adopted by LAs

As can be seen in Table 1, LAs use a range of discursive devices in response to learners’ work. However, the focus of the present research into the degree of directiveness of written advising was inspired by the results of Mynard’s (2010) study which indicated that 15% of the discursive devices were categorized as “giving input.”

The Present Research

For this study, the researchers drew on the same data set as above, but were interested in a more in-depth analysis of the ways in which LAs actually gave input to learners. As a result, the following research question was created:

How do LAs give directive and non-directive written input to learners on language learning methods, strategies and planning?

Whereas in the previous study, thirty learner module packs were analysed from the eight-week program, for the present study just seven module packs from the previous study were used in order to make the research manageable. One pack from each LA involved in the previous study was selected at random to ensure that each LA was represented in the data analysis, but individual styles are not taken into account. In fact, different approaches to advising may be taken by the same LA at different times depending on the needs of a particular learner. However, the intention of the present study is not to examine differences in advising styles. Rather, the purpose is to conduct a closer analysis of the written discursive devices in order to understand the degree of directiveness the team of LAs adhere to when providing input to learners on planning and implementing an individualized self-directed learning plan.

All of the handwritten comments made by the learning advisors had already been transcribed for the previous research and the seven selected module packs were completely reanalysed for the present research using a piece of qualitative analysis software called HyperRESEARCH. HyperRESEARCH enables items to be easily coded manually on text files by researchers. The software allows researchers to see items grouped by code – either as a list, or in context – in order to aid analysis.

Although discursive devices written for purposes other than giving input were discounted from the data, the authors would like to note here that the comments made by the LAs served a variety of purposes, not just giving input (see Table 1). For example, there were many cases where LAs wrote comments which sought clarification, summarized the work so far, attempted to motivate or encourage the learner or aimed to help the learner think more deeply about the learning process in general.

Data Analysis

Only the items in the data which were identified as serving the purpose of “giving input” were chosen for analysis and there were 161 instances of “giving input” altogether in the seven packs. Instances of “giving input” and possible emergent themes were discussed by the two researchers until ten codes were agreed upon. The codes were then classified as either “directive advising” or “less-directive advising” through a process of discussion and detailed examination of the data. Table 2 shows the discursive devices which the researchers classified as directive advising. Table 3 contains the discursive devices coded as less-directive advising.

Table 2. Discursive devices coded as “directive advising”

| Code | Purpose | Example from the data |

| 1. Directive | LA notices an important point and tells the learner what to do | “You must make sure that when you speak to practice grammar items that you try to use the grammar items you were studying” |

| 2. Strong suggestions | LA gives a concrete example of a study material, direction or strategy often using “you should…” | “you should think about how you can evaluate your overall progress in this module” |

Table 3. Discursive devices coded as “less-directive advising”

| Code | Purpose | Example from the data |

| 3. Prompting further reflection (PFR) | LA wants to highlight an important issue and see if the learner can identify a problem, connection, study material or strategy by themselves | “Are the sentences you are using for shadowing really useful for your speaking skill?” |

| 4. Conditional language | LA provides examples of activities, materials and possible outcomes using conditional language “if…” | “If you talked about the same topic with another teacher, you might hear similar vocabulary” |

| 5. Mild suggestions | LA uses expressions such as “maybe you could…” and “you might want to…” in order to give suggestions, but transmits the message that the learner should be the one to decide the best course of action. (This kind of alluding technique is similar to that in counselling noted earlier by Feltham (1995).) | “I think it’s a good idea to review this week” |

| 6. Expert opinion | LA explains in general terms why something is effective or not effective. | “Learning vocabulary for the sake of learning vocabulary is not very effective” |

| 7. Intuiting | LA makes guesses based on available information and reflects the issue back to the learner. | “You didn’t write clearly in your learning plan but it seems you want to focus on improving your speaking skills and vocabulary skills for now” |

| 8. Restating | LA paraphrases what the learner has written about or done in order to highlight it. In written form, this is almost always followed by another discursive device. Together the two devices provide input relevant to the learner. | “You mentioned that one of the worksheets was too easy” (followed by “so you might want to challenge yourself with something more difficult”) |

| 9. Reinforcing | LA paraphrases the learner or describes what he/she has done and provides positive feedback letting the learner know that he/she is on track. | “I think that is a good strategy to try to explain the words you learned in your own words.” |

| 10. Reorienting | LA paraphrases the learner or describes what he/she has done, but the message is clear that the learner should choose another approach. | [1]No occurrences in the present data set. General example: “So, you decided to work on your pronunciation skills this week. Don’t forget that your goal is listening” |

During the initial coding stage, the “expert opinion” code was assumed to be a directive device. However, on closer examination of entire segments of text, this code was found to be a more subtle intervention device similar to the one described by Maynard (1991). The LA makes a general comment about good cognitive strategies or ways to organise self-directed work, but the learner can choose whether or not to adopt it.

Results

Before examining some of the discourse more closely in context, it is useful to see some broad trends. Figure 1 shows the number of times that the LAs (collectively) adopted the written typologies described in tables 2 and 3 in the eight-week period, although there was variation between the individual LAs regarding the extent to which they used the various discursive devices for giving input.

Figure 1: The total number of times LAs adopted the different written discursive devices

The following section will provide snapshot details of the three most heavily used devices followed by a more in-depth look at the data by presenting actual extracts and their respective codes.

Prompting further reflection (PFR)

Prompting further reflection (PFR) was the most frequently used device for giving input to learners. Figure 2 shows the number of times in which the individual LAs used PFR by asking questions with the specific purpose of giving indirect input throughout the eight-week period.

Figure 2. The total number of times each LA used PFR for giving written input

All but one of the LAs used PFR as a discursive device in order to give input. The extracts presented later in the paper give examples of how PFR is used in context.

Expert opinion

All of the LAs gave an “expert opinion” at least once in the eight-week period and this is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The total number of times each LA gave an expert opinion as a device for giving input

Extracts 4 and 5 presented later in the paper show how expert opinions were introduced as a non-directive discursive device in context.

Directives

All but one LA used at least one directive as a way of giving input to a learner as can be seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4. The total number of times each LA used a directive as a device for giving input

Extract 5 written by LA 1 examined later in the paper shows an example of a directive being used in context.

Analysis of the discourse

By examining whole segments of comments written by LAs in context, the researchers were able to see how an LA responded to a learner’s self-directed work by drawing on a range of discursive devices. The following example extracts were chosen because they show a variety of the discursive devices being used concurrently.

Extract 1 (LA 2)

Extract 1 is from a longer written segment by LA 2. The learner was working on improving English conversation skills and had described how she had recorded her conversation with a partner in order to later notice problematic areas in her speaking skills during the conversation. The student had noticed that the conversation was one-sided. From her side there was a lot of silence or one-word responses to the interlocutor. In the module pack, the learner wrote about her idea to prepare topics in advance for the next time.

In Extract 1, the LA writes a series of questions in order to prompt further reflection (lines 1 to 5). The LA then finishes the thread by providing some reinforcement and encouragement to the learner to reassure her that she is doing well (lines 6 and 7).

Extract 2 (LA 3)

This extract is the written response by the LA to the learner who had written detailed notes about her study plan, but her study approach did not involvetrying to use the new words in her speaking practice (which was her goal).

The LA begins with some encouraging words and writes a reinforcing comment on something that the learner did particularly well (lines 1 and 2). The LA intuits that the learner is learning a lot of new words each week. The assumption here is that the LA thinks that the learner may be learning too many new words, but uses an indirect way of expressing this and asks a question to encourage the learner to reflect on whether the words are useful (line 3). The LA follows up by intuiting that the learner may need to shift the balance from studying new language to actually using the new words (line 5). The LA then asks a question in order to encourage the learner to reflect on how the words could be used (lines 6-7).

Extract 3 (LA 5)

The following extract is from an LA on a learner’s first week of self-directed work. The learner’s work was rather unstructured and he had only just begun to locate and experiment with using different strategies and resources.

This extract begins with an encouraging comment from the LA (line 1). Next, the LA asks a series of questions (lines 2-6). The implication behind these questions are that the LA thinks that the learner may not be choosing appropriate vocabulary, is not using appropriate resources and is giving no indication that he is attempting to keep records or review the new words. However, instead of pointing out these deficiencies, the LA asks questions to encourage the learner to come to these conclusions for himself. The LA then refers to an activity that the learner has done well (line 7). Finally, the LA follows this up with a question in order to encourage the learner to think more deeply about the activity (line 8).

Extract 4 (LA 6)

In this extract, the learner wrote very detailed notes and seems to be a fairly aware, independent learner who is on the right track with her self-directed learning. The learner is focussing on improving listening skills.

As this learner appears to be managing her self-directed learning well, the LA does not need to provide much input. The main purpose of the discursive devices used in this extract is to encourage the learner and reassure her that she is on track. However, there was one aspect of the learner’s work that the LA highlighted (lines 4-6). The LA does not give suggestions about what the student could do to increase listening opportunities, but instead attempts to elicit ideas from the learner. The use of two “expert opinions” (lines 8 and 10) highlight to the learner the importance of confidence-building and vocabulary-building.

Extract 5 (LA 1)

This extract shows a more directive approach in action with a learner who appeared to need more direction from the LA. The learner is not balancing her learning activities well. Her goal is to improve her speaking skills by focusing on grammar, but she appears to be focusing exclusively on grammar study and not at all on her speaking skills.

This extract was taken from week 3 of the learner’s self-directed work. In the previous two weeks, the LA has used a range of less directive discursive devices, but as the learner continues to lack focus, the LA becomes more directive in this instance. The LA begins (as usual) with encouragement (line 1), then asks a question about whether the learner is using the grammar that she had studied and whether it had been effective (lines 2 and 3). Presumably, the LA suspects that the learner has not been practicing speaking at all, but instead of confronting the learner, the LA chooses to ask questions that prompt further reflection. The LA then makes a general statement about good practice for self-directed learning (lines 4-5) but follows up with a request for the learner to explicitly state how well she is balancing her learning activities the following week. Presumably, the LA hopes that by focusing on the balance, the learner will then be able to make her own connections about effective learning. The LA asks several other questions (lines 8-11) and finishes by apologizing for the questions and encouraging the learner for the following week.

Limitations

Clearly, there are several limitations associated with this study. Firstly, it is a small study involving just seven learning advisors providing comments on work over an eight-week period in one particular context so broader applications may be limited. Secondly, although the authors have attempted to provide background to the learners’ work and progress, the data only shows the advisors’ part in the ongoing dialogue. Advising is reported to be a process of co-construction of knowledge (Karlsson, 2008) and a process of negotiation and interaction (Mozzon-McPherson, 2001). Analysis should ideally take into account both participants’ contributions to the dialogue. Further analysis is planned which takes these dialogic implications into account. Thirdly, the researchers are only making assumptions about the LAs’ intentions for the written advising approaches and there would have been benefits to interviewing the LAs (which was not practical for the present research). Finally, the extracts have been presented in isolation without access to information on the previous and on the further development of the self-directed learning program. Further analysis is planned and the researchers intend to track one learner and one advisor throughout the module and self-directed learning process in order to investigate the co-constructed relationship of this kind of advising. Despite these limitations, the data has provided some indications of the ways in which LAs provide input to learners in written form which will be useful for training learning advisors and discussion on written advising practices.

Conclusions and Discussion

Through the analysis of written advising, the authors have attempted to show how a team of LAs give advice in written form to learners on their self-directed work. Although this study has its limitations, some interesting observations can be drawn. Firstly, in the analysed corpus there were no obvious fixed patterns of written advising. LAs appeared to either favour different discursive devices, or were responding to what they thought would most benefit the learner at the particular stage that he/she was at with his/her self-directed learning. The second observation was that the LAs appeared to negotiate the more directive-less directive continuum much as the counsellors did in Candlin and Lucas’ (1986) study. The discursive devices were generally non-directive, but became more directive when a learner appeared not to benefit from the more subtle interventions introduced in previous weeks.

What appears to be indicated by this small study and the previous research into how written advising influenced self-directed learning (Mynard, 2012) is that (1) it is appropriate for LAs to use more directive and less directive discursive devices according to the needs and levels of awareness the students have at a particular time and (2) LAs appear to be instinctively targeting their written advising to the learners’ needs and levels of awareness of the learning process.

Conducting research on written advising has a number of benefits for the advising team. Firstly, the findings are reassuring for the LAs as they indicate that LAs are responding to students’ needs. Secondly, the team of LAs are able to broaden their awareness and skills of written advising through the examination of the kinds of discursive devices that other LAs use. Thirdly, this kind of information is useful for training new advisors who are often insecure about the comments they are writing and whether or not they are actually helpful for the learners.

Notes on the contributors

Jo Mynard is the Director of the Self-Access Learning Centre and Assistant Director of the English Language Institute at Kanda University of International Studies in Japan. She holds an M.Phil. in Applied Linguistics from Trinity College, Dublin and an Ed.D. in TEFL from the University of Exeter (UK).

Katherine Thornton is a Learning Advisor and Academic Coordinator of the Self-Access Learning Centre at Kanda University of International Studies in Japan, and also serves as President of the Japan Association of Self Access Learning. She holds an MA in TESOL from the University of Leeds (UK).

References

Candlin, C.N., & Lucas, J. (1986). Interpretations and explanations in discourse: Modes of “advising” in family planning. In T. Ensink, A. van Essen & T. van der Geest (Eds.), Discourse analysis and public life (pp. 13-38). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Foris.

Carson, L., & Mynard, J. (forthcoming). Introduction. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Colledge, R. (2002). Mastering counselling theory. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave McMillan.

Cooker, L. (2010). Some self-access principles. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 1(1), 5-9.

Egan, G. (1994). The skilled helper: A systematic approach of effective helping. Pacific Cove: Brooks/Cole.

Feltham, C. (1995). What is counselling? The promise and problem of talking therapies. London: Sage.

HyperRESEARCH Qualitative Analysis Tool (software) (version 2.8.3). Available from http://http://www.researchware.com/

Karlsson, L. (2008). Turning the Kaleidoscope – (E)FL educational experience and inquiry as auto/biography. University of Helsinki, Faculty of Arts, Department of English.

Maynard, D. W. (1991). Interaction and asymmetry in clinical discourse. American Journal of Sociology, 97(2), 448-95.

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2001). Language advising: Towards a new discursive world. In M. Mozzon-McPherson & R. Vismans (Eds.), Beyond language teaching towards language advising (pp. 7-22). London: CILT.

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (forthcoming). The skills of counselling: Language as a pedagogic tool. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and context. Harlow: Longman.

Mynard, J., & Navarro, D. (2010). Dialogue in self-access learning. In A. M. Stoke (Ed.), JALT 2009 conference proceedings (pp. 95-102). Tokyo: JALT.

Mynard, J. (2010). Promoting cognitive and metacognitive awareness through self-study modules: An investigation into advisor comments. Proceedings of the International Conference CLaSIC 2010 “Individual Characteristics and Subjective Variables in Language Learning”, Singapore, 2-4 December 2010, pp. 610-627.

Mynard, J. (2012). Written advising strategies in self-directed learning modules and the effect on learning. Studies in Linguistics and Language Teaching, 23, 125-150.

Nelson-Jones, R. (2008). Basic counselling skills – a helper’s manual (2nd ed.). Sage: London.

Noguchi, J., & McCarthy, T. M. (2010). Reflective self-study: Fostering learner autonomy. In A. Stoke (Ed.), JALT2009 Conference Proceedings (pp. 160 – 167). Tokyo: JALT.

Rogers, C. (1951). Client-centred therapy. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Silverman, D. (1997). Discourses of counselling: HIV counselling as social interaction. London: Sage.

Thornton, K., & Mynard, J. (forthcoming). Investigating the focus of advisor comments in a written advising dialogue. In C. Ludwig & J. Mynard (Eds.), Autonomy in language learning: Advising in action. Canterbury, UK: IATEFL.

Yamaguchi, A., Hasegawa, Y., Kato, S., Lammons, E., McCarthy, T., Morrison, B.R., Mynard, J., Navarro, D., Takahashi, K., & Thornton, K. (forthcoming). Creative tools that facilitate the advising process. In C. Ludwig & J. Mynard (Eds.), Autonomy in language learning: Advising in action. Canterbury, UK: IATEFL.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Christopher Candlin for his ongoing advice on the discourse of advising in language learning, to Maria Giovanna Tassinari Pfeiffer and the two anonymous reviewers for their detailed comments on an earlier draft of this paper, to Moira Hobbs for facilitating the blind review process on behalf of the authors (who are also the editors of this special issue), and to Kentoku Yamamoto for his perceptive comments and excellent proofreading.

[1] Although no occurrences of this code were found in the present data set, the authors have included it here for two reasons: (1) it occurred in an noticeable number of packs not included in the data set (2) it emphasizes the contrastive role of the preceding discursive device, i.e. “Reinforcing” provides feedback to the learners that they are following an effective course of action; “Reorienting” provides feedback which suggests that a learner is not following an effective course of action.

Pingback: Published: The degree of directiveness in written advising « ELI at Kanda University of International Studies